Building from DC’s model, Quantified Ventures launched a competition with Rockefeller Foundation and Neighborly to issue EIBs in two more US cities. Atlanta is the first to win this competition, funding eight green infrastructure projects for a total of $12.9 million. Baltimore is now looking to do the same. It will be a few years before we see the performance results in DC, and cannot yet measure the success of EIBs to fund green infrastructure projects. However, exploring innovative financing mechanisms for green infrastructure projects is an important measure to entice investors and quantify community and environmental benefits of green infrastructure.

|

As cities across the country look more and more to investing in widespread green infrastructure, they must explore innovative ways to finance these new techniques. Traditionally, major grey infrastructure projects such as tanks and tunnels are paid for through a municipal bond, which the municipality will pay off over time through revenue generated through the water bill (in NYC’s case) or taxes. Environmental Impact Bonds (EIB) differ from municipal bonds as they use a “Pay for Success” approach, sharing performance risks with private investors. DC was the first city to trial an EIB last year. The tax-exempt bond finances DC to pilot green infrastructure projects, with an interest rate dependent on the performance of the green infrastructure project.

Building from DC’s model, Quantified Ventures launched a competition with Rockefeller Foundation and Neighborly to issue EIBs in two more US cities. Atlanta is the first to win this competition, funding eight green infrastructure projects for a total of $12.9 million. Baltimore is now looking to do the same. It will be a few years before we see the performance results in DC, and cannot yet measure the success of EIBs to fund green infrastructure projects. However, exploring innovative financing mechanisms for green infrastructure projects is an important measure to entice investors and quantify community and environmental benefits of green infrastructure.

0 Comments

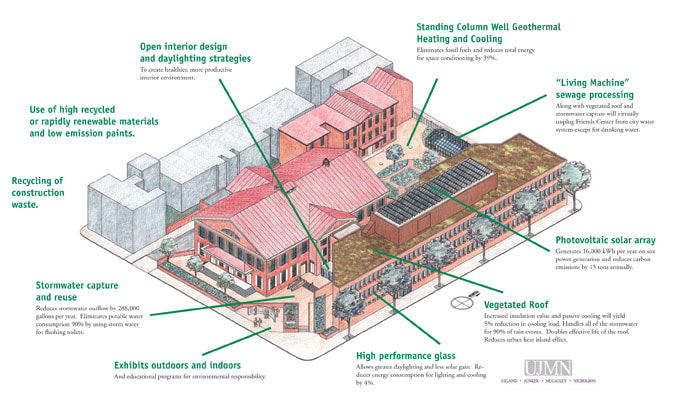

On Thursday October 19th, NYC Soil & Water Conservation District is having its 7th Annual Green Infrastructure Bus Tour, this year in Philadelphia! Like New York City, Philadelphia is on a combined sewer system. In 2011, the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) released Green City, Clean Waters, establishing a goal to “green” 10,000 acres with green infrastructure. Paired with incentives for private property owners and a new stormwater billing system, green infrastructure installations are now abundant in Philadelphia, on both public and private properties. This year’s tour will have five stops including a pump house with a green roof, a community environmental center, an industrial site turned park on a college campus, a stormwater capture and reuse system at a Quaker House, and a rain garden managing stormwater from a highway. Get your tickets for the tour here! Venice Island Performing Arts and Recreation CenterIn 2014, the Philadelphia Water Department and Department of Parks and Recreation opened the Venice Island Performing Arts & Recreation Center. The performing arts center is a significant improvement from the aging playground and rec center once there, and features stormwater management practices on and under the site. Underneath Venice Island is a four million gallon stormwater retention basin, with a green roof on its only above-ground feature, the pumphouse. The parking lot is bounded by stormwater tree trenches, and the lot surfaces itself are permeable. Also on the site are basketball courts, an outdoor amphitheater, and a spray park. Venice Island is a great showcase for a comprehensive stormwater management project that meets the needs of the community. For more information, visit: www.phillywatersheds.org/category/blog-tags/venice-island Overbrook Environmental Education Center Overbrook Arts and Environmental Education Center was founded in 2006 by former PWD employee, Jerome Shabazz. The Center itself was built on a brownfield site and serves and strengthens the environmental justice communities of Overbrook and Wynnefield. Jerome’s vision with the Overbrook Arts Center is to provide opportunity for young people in the community to get hands-on experience with stormwater and other environmental projects. The Center has a greenhouse, a warehouse for a future farmers market, and manages 100 percent of stormwater that falls on all three lots. The 45,000 square foot site manages 30,000 gallons of stormwater in a one inch storm through bioswales, a green roof, stormwater planters, and pervious pavement, all designed and installed by Jerome, his students and some technical assistance. For more information, visit: www.overbrookcenter.org Penn ParkPenn Park is a public park on University of Pennsylvania’s (Penn) campus in West Philadelphia, designed by Van Valkenburg. Penn worked with Amtrak and SETPA, whose tracks surround the site, PWD and the Streets Department to design and construct new athletic fields on an old USPS vehicle maintenance facility and parking lot. The park opened in 2011 and align with Penn’s broader master plan, which goes above and beyond Green City, Clean Waters. The park manages about an inch and a half of rain through bioswales, over 500 newly planted trees, and meadow plantings. These landscape features complement the 300,000-gallon cistern underground that captures stormwater from the turf fields to reuse for irrigation. The meadow and bioswale landscape were chosen (in lieu of only underground cisterns) to showcase landscape typologies. There is also a food orchard in collaboration with the Philly Orchard Project and student-run apiary for on-site research and education. For more information, see this case study from ULI. Friends Center; The Quaker Hub for Peace & Justice in PhiladelphiaThe Friends Center is a green building that features geothermal heating and cooling, solar panels, stormwater capture and reuse, a green roof and more. Rainwater from the meetinghouse rooftop is captured in cisterns, and used for flushing the toilets in the office building. The office building itself is covered with a green roof, cooling the building in the summer and extending the lifetime of the roof. Find out more about the Friends Center here: www.friendscentercorp.org I-95 Green InfrastructureThree rain gardens line Richmond Street in Fishtown, underneath the highway I-95. Developed by PennDOT, Villanova University and Temple University, these gardens are a pilot to see how rain garden plantings survive with road salt, oil, and other highway stormwater contaminants.

The gardens are designed to manage 1.5 inches of rainfall over a 45,000 square foot drainage area, but have proven to manage more than that. Collectively, the gardens can manage over 32,000 gallons of stormwater from entering the combined sewer system. A larger phase is in the works, with the designed capacity to manage 1.2 million gallons of stormwater per storm. This site does not have a tour guide scheduled, and we will only stop here if time allows. Check out this recent article in Philly.com  Historic Fourth Ward Park 2005 - 2015; photos from Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy Historic Fourth Ward Park 2005 - 2015; photos from Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy Atlanta, GA is mostly on a combined sewer system. In 1999, the City of Atlanta signed a consent decree with the EPA to manage its chronic CSO issues. The City proposed a 15-year $3 billion plan to construct a CSO tunnel and sewer separation in selected areas. While grey infrastructure has been at the forefront of Atlanta's CSO mitigation plans, a major green infrastructure project in the Old Fourth Ward neighborhood is contributing to Atlanta's CSO reduction goals. The Historic Fourth Ward Park, just Northeast from downtown Atlanta, is a new 17 acre park with a 2 acre detention pond that diverts stormwater from entering the combined sewer system. Before the park was constructed, the Fourth Ward was subject to intermittent flooding and sewer overflows. As part of its 2001 plan for sewer system improvement, the City initially planned to build out a tunnel extension of the combined sewer system. In 2003, a stormwater activist developed a plan to turn this brownfield site into a park. After nearly a decade of planning, land acquisition and finally construction, the historic Fourth Ward Park was completed in 2011. The park is a stormwater detention basin that manages stormwater in the 800-acre drainage basin for Clear Creek. There is a permanent pool of water in the pond that takes on stormwater runoff from up to a 100 year storm. The water is detained during a storm and slowly is released into the Highland Avenue Combined Sewer Trunk, where it would eventually be treated at a wastewater treatment plant. Other features in the park are a fountain using captured stormwater within the pond, a skate park designed by Tony Hawk, and an amphitheater. The park has been a major amenity for the community and visitors, and has spurred economic development along the beltline, all while advancing the City's ability to meet Federal Consent Decree requirements. Furthermore, the creation of a detention pond instead of a CSO tunnel helped the city save more than $5 million in infrastructure costs. The park also borders the Beltline Greenway, a 22-mile multi-modal loop currently underway in Atlanta. Visit the Historic Fourth Ward Park Conservancy's website for more information about the park and its history. It's important to acknowledge the history of the neighborhood where this massive infrastructure project took place. The Fourth Ward was historically an African-American community and the birthplace of Martin Luther King Jr. What was previously dilapidated buildings and industrial contamination has been transformed to upscale residential development. There have been rising concerns that the existing residents will be pushed out, especially as the Beltline project progresses and housing becomes unaffordable. There is much more discussion on the Beltline and gentrification, starting with this article. Gentrification has been an ongoing concern for Atlanta and cities all over the country that are facing resurgence and increased popularity. While housing and affordability is beyond the scope of NYC Soil & Water Conservation District's work, it is crucial to recognize the importance of comprehensive planning and creating public spaces and environmental amenities that are accessible to everyone.

Atlanta has many other green infrastructure projects, including a green roof on City Hall and a solar PV + rainwater harvesting + green roof on the Southface Energy Institute. Next time you're in Atlanta, check out some more green infrastructure projects from the City's Self-Guided Green Infrastructure tour guide. Backyard green infrastructure projects can be simple and cheap, depending on what kind of project you'd like to do, while helping reduce stormwater from entering the combined sewer system and polluting our waterways. Check out this blog post from Maryland that debunks some of the myths you may have heard about green infrastructure. If installed properly and maintained well, your green infrastructure won't become a breeding ground for mosquitoes and doesn't have to cost a fortune.  Earlier this year, we put together a Green Infrastructure Guide for Private Property Owners, full of resources specific for NYC homeowners. There are also plenty of online guides for DIY green infrastructure projects, such as GrowNYC's Green Infrastructure Toolkit, and IOBY's Guide to Green Infrastructure. We'd love to hear how your green infrastructure project goes, and connect you to any resources you may need in the process. Contact: korin@nycswcd.net The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has just released guidelines for collaboration, funding and community engagement to accomplish green infrastructure in parks. The guide looks at case studies in Indianapolis, Philadelphia, New York City and other cities to exemplify the following process:

1. Identify and Engage Partners 2. Build Relationships 3. Leverage Funding Opportunities 4. Identify Green Infrastructure Opportunities 5. Plan for Maintenance 6. Undertake High-Visibility Pilot Projects Read the full guidelines here. Green infrastructure for stormwater management has a broad range of benefits. Green job opportunities, improved air quality, reduced flooding, increased habitat and green space for communities are some of the commonly listed benefits that green infrastructure has for urban environments. These co-benefits are starting to be evaluated in the financial sector, as demonstrated in a landmark contract between DC Water and financial investors.

DC Water is Washington DC’s water and sewer authority, managing drinking water, wastewater and stormwater for the district. In 2005, DC entered a consent decree with the EPA to reduce CSO by 96% by building out more grey stormwater infrastructure like tunnels. In 2016, DC Water and the EPA modified and extended the consent decree to allow DC to pilot green infrastructure practices in lieu of building underground tunnels. That’s when DC Water was able to contract with Calvert Foundation and Goldman Sachs for the world’s first Environmental Impact Bond or EIB. The structure of this bond is similar to a Pay-for-Success (PFS) Bond or Social Impact Bond (EIB). The financing mechanisms are a bit complicated but have generated much enthusiasm for investors. The DC Water EIB is a tax-exempt bond that will allow DC to pilot green infrastructure, create green jobs, and pay back the bond with interest rates dependent on its success. Calvert Foundation and Goldman Sachs are the investors, fronting the capital for DC Water to implement green infrastructure. DC Water must meet the agreed upon goals: install green infrastructure to manage 1.2 inches of rainfall on nearly 500 acres of impervious area. Of the jobs created, 51% must be District residents certified through DC’s Green Jobs Program. If DC Water meets the agreed-upon goals as expected, they will pay back the $25 million dollar bond at a 3.43% interest. If DC Water outperforms, meaning their green infrastructure has larger CSO reductions than anticipated, Calvert Foundation and Goldman Sachs get a higher return on investment (DC Water pays a higher interest rate). If the green infrastructure doesn’t work or does not meet their expectations, DC will pay back with a smaller return and will likely discontinue future green infrastructure projects and go back to investing in grey infrastructure. Learn more about DC Water’s consent decree or the DC Water Environmental Impact Bond. |

District Staff

We are the people who run the programs. Archives

August 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed